Asalaamu alaykum,

Module two has been deeply concentrated on the concept of إِعْرَاب which focuses on the case endings of words. Previously we have looked at nouns which are مَبْنِيْ (indeclinable – unable to accept changes to its ending). This post looks at the case endings of nouns which are مُعْرَب (declinable).

If we remember in the beginning, النَّحُوْ (syntax) involved looking at the relationship between words in a sentence and working out the forms of words by analysing their endings. It is through analysing their endings that we can understand their role within a sentence. Within Arabic there are three types of words: particles, verbs and noun. On a spectrum of declinability, particles are the least declinable and nouns are the most declinable.

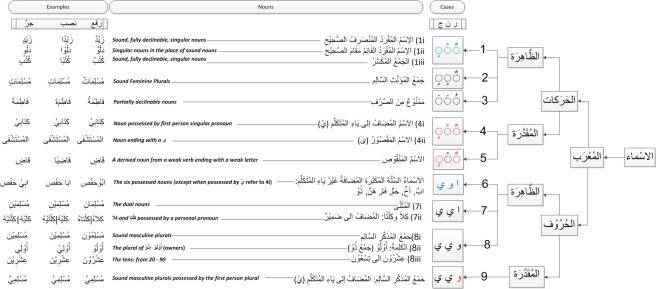

What do I mean by declinability? Whether words are able accept changes to their endings to represent what case they’re in. From the graph above we can see that nouns are most declinable. But do they all show their رفع, نصب, and جَر state in the same way? The answer is a big no. Rather, different nouns have different signs for a particular case. Signs? Yes, signs. Signs are the way in which we can identify what case a declinable noun is in. These signs could be through diacritics (حَرَكات) or letters (حُرُوْف). There is a standard (أَصَل) for each sign. For signs by diacritics, it’s ٌ ً ٍ and for signs by letters it’s ا ي و. Depending on whether the noun shows its case through diacritics or letters, these two combinations are the standard. If a noun cannot take the standard combination then this is when we deviate from the standard combinations. As such, there are 4 deviations for diacritics and 3 deviations from the letters. In total we have 9 combinations (including the two standard combinations). The following chart is a breakdown of each combination and the type of noun which uses each specific combination. It includes example for each combination also, which is very useful to memorise.

The rest of the post is an elucidation of this chart so it is imperative that you have a look at it for context. I would recommend clicking on the chart to enlarge, also.

Combination 1

This is the standard أَصَل set of diacritic combinations, therefore there are three types of nouns which use them. The first group are sound, singular, fully declinable nouns which have no weak or hamzated letters. The second group are singular nouns which have a weak letter at the end that is preceded by a letter with a sukoon on it making it in the place of sound noun.

– An important sidenote: weak nouns are not identified in the same way as weak verbs. Weak verbs have a weak letter حَرْفُ العِلَّة as part of the root letters (ا ي و). It can be in the beginning مِثَال, middle أَجْوَف or end ناقِص. Nouns on the other hand are only identified as weak if the last letter has one of the حَرْفُ العِلَّة or a hamza AND if the letter preceding it is مُتَحَرِّك (has a harakah on it). The first group had no weak letters or a hamza and therefore was classified as sound. The second group however has a weak letter at the end (therefore ناقِص verb) and is preceded by a ساكِنَة (letter with a sukoon on it). It is therefore classified as a noun which is not completely sound due to the weak letter at the end but is considered as ‘in the place of sound’ due to the ساكِنَة before it.

The final subgroup for combination 1 is broken plurals جَمْعُ المُكَسَّر. This is where the sequence of root letters are broken from the singular to the plural, for example رَجُلٌ becomes رِجَال andكِتَابٌ becomes كُتُبٌ.

Combination 2

This combination of diacritics is applied to words which are sound feminine plurals حَمْعٌ المَكَسَّر السَّالِم. A group of nouns we are familiar with by now. But just for the sake of revision, an example is : مُسْلِماتٌ, مُسْلِماتٍ, مُسْلِماتٍ

Combination 3

This combination is used for words which are partially inflected. This is a group of nouns that we haven’t touched upon as much. If you remember back in previous posts I’ve mentioned rules such as feminine names do not take التَّنْوِيْن or الكَسْرَة and here’s why:

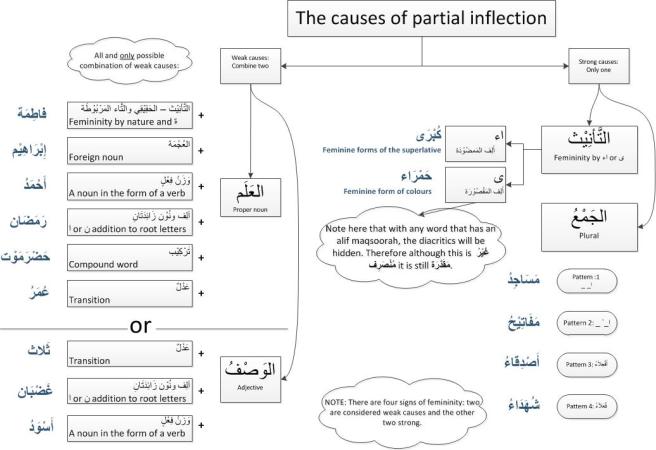

A noun is partially inflected when it has been affected by two weak causes or one strong causes. Causes? Yes causes. There are 9 causes in Arabic which can render a noun as partially inflected; meaning it shows it رفع case through dhamma and the نصب and جرّ case through fatha – as outlined in the chart. The causes are split into weak and strong. Where the causes are weak, they need to combine with another weak cause. Where the cause is strong, it is sufficient to render the noun partially declinable – غَيْرُ مُىْصَرِف. The following chart is a full breakdown of the causes of partial inflection.

Note: If the partially inflected noun has an ال attached to it then in this case it can take a kasra.

Combination 4

This combination consists of diacritics which are hidden in all these cases and the type of nouns this occurs to are of two types. Firstly nouns which have been possessed by the singular first person personal pronoun يْ. To ease pronunciation any noun preceding this pronoun will have a kasra. The second group of nouns are where their diacritics are hidden are nouns because they end with an الِف المَقْصُوْرَة: ى . If you looked at the chart in combination 3 you will identified that this الِف المَقْصُوْرَة – ى came up in عَيْرُ المُنْصَرِف also. So what’s the difference? It’s quite simple, if the الِف المَقْصُوْرَة – ى is not part of the root letters of a noun then it is a sign of femininity and renders the noun غَيْر مُنْصَرِف. If, however, the الِف المَقْصُوْرَة – ى is part of the root letters, then it is no longer considered a sign of femininity but rather the noun remains masculine and falls under the group of nouns which decline in accordance to combination 4.

Remember: in both combinations 3 & 4, the diacritics are still hidden. The difference lies in what diacritics are hidden.

Combination 5

Combination 5 is used by nouns which are derived from weak verbs where the حَرْفُ العِلَّة – ا ي و is the last root letter or better known as the لام الكَلِمَة. These nouns in question are derived from ناقِث verbs. Nouns derived from ناقِص verbs are called الاسْمُ المُشْتَق. This combination we are looking at a particular types of derived noun and that’s the active noun – اسْمُ فاعِل.

In this combination, note that the in the رفع and جرّ case the weak letter is not there and therefore the diacritic is hidden. However, in the نصب case the weak letter reappears and thus the diacritic is also apparent. Therefore the نصب case is actually apparent in this combination whereas the رفع and جرّ are hidden. Let’s take an example:

The rule to understand from the get go concerning الفِعْلٌ النَّاقِص is this: if a weak letter has a strong diacritic like dhamma on it then you get rid of the harakat, so the letter remains with a sukoon.

Let’s take the weak verb ‘to cure’: شَفَا, يَشْفِيْ

Past tense: شَفا was originally شَفَيَ from the category ضَرَبَ, يَضْرِبُ:

In Arabic if there is a letter with a fatha on it with a weak letter after it, then the weak letter always wants to copy it and have a fatha too. Therefore: شَفَيَ becomes شَفَا because two fatha’s equal an alif.

Present/Future tense: يَشْفِيْ was originally يَشْفِيُ:

In Arabic weak letters cannot take a dhamma as mentioned above. When this happens you take off the harakat and you are left with a sukoon on it. Therefore: يَشْفِيُ becomes يَشْفِيْ

Active noun (اسْم الفَاعِل):

Now for the الاسْمُ المُشْتَق (derived noun from الفِعْل النَّاقِص), specifically اسْمٌ الفَاعِل (the active noun).

شافٍ was originally شَافِيٌ in the رفع

Now, if you remember what I said, weak letters cannot have a dhamma on it and in this case it has a tanween on it. The thing about tanween is that it’s made up of a letter with a with a fatha, dhamma or kasra followed by a nun with a saakin. So in this case يٌ is actually: يُ + نْ. Therefore: شَافِيُنْ

So as per the rule, we take of the dhamma from the yaa and we are left with:

شافِيْنْ

The next rule you need to remember is that when you have 2 sukoons you knock of the first one along with the letter. And you are left with:شافِنْ. What do we have here? A letter with a harakah on it followed by a nun with a sukoon – therefore a tanween – and more specifically a kasratayn (because the harakah on the letter is a kasra). So this becomes شافٍ.

This is how the dhamma is hidden in the رفع case for weak nouns. Let’s look at the نصب case now with the same steps:

1 شافِياً

There’s actually no problems with this one. Why? Well, a weak letter with fatha preceded by a letter with kasra poses no problems phonetically and thus it is left as it is with no changes. And as the fatha is clearly visible and not taken off, the نصب case is therefore apparent (الظَّاهِرَة) for this combination.

Finally the ّجر case. We go through all the steps as we did for رفع case:

1 شَافِيٍ – tanween on weak letter too heavy

2 شَافِيِنْ – take of the harakah on the weak letter

3 شَافِيْنْ – two sukoons so take of the first one with the letter

4 شَافِنْ – Left with مُتَحَرِّك plus نُوْن ساكِنَة

5 شَافٍ – So join to make a tanween

Alas, you arrive to the conclusion شافٍ.

So that’s how weak nouns from الفِعْل النَّاقِص work in terms of declinability. I hope that’s made it easier to understand. If you didn’t quite understand the processes then just internalise that: weak nouns derived from الفِعْل النَّاقِص have their diacritics hidden in the رفع and جرّ case due to dropping the weak letter but it is shown in the نصب case from not dropping the weak letter.

Weak verbs are actually from the next module but our teacher likes us to understand the background behind rules – even if it means jumping modules. We will have an extensive post on this in the near future, inshaAllah.

Combination 6

So, we are now on the last four set of combinations. These combinations look at case represented in nouns through letters. This combination displays the أَصَل – standard. The group of nouns which use this combination are specific group of 6 nouns:

ابٌ – Father

أَخٌ – Brother

حَمٌّ – Brother in law

فَمٌ – Mouth

هَنٌ – This word is usually used instead of naming something or something.

ذُوْ – Possessor of e.g. ذُوْ الجَلالِ والإكْرَام The possessor of honour and majesty, Allah (swt).

So what does ا ي و have to do with these words? Well, when they are used in the position of مُضَاف and therefore are possessed then you have to add one of these weak letters for the respective case that you are expressing.

The father of Bakr came – جاء ابُوْ بَكْرٍ

I saw the father of Bakr – رَأيْتُ ابا بَكْرٍ

I passed by the father of Bakr – مَرَرْتُ بِابِيْ بَكرٍ

The only time these changes do not occur is when any of these six nouns are مُضَاف to the first person personal pronoun يْ, then you would resort to combination 4i.

Additional points: These words are not used in the diminutive form (put into the فُعَيْل form). The م in فَمٌّ drops when put into مُضَاف position. Lastly, ذُوْ cannot be مُضَاف to a ضَمِيْرٌ – (personal pronoun).

Combination 7

Combination 7 is applied to two groups of nouns. The first being words in the dual form e.g. مُعَلِّمانِ, مُعَلِّمَيْنِ, مُعَلِّمَيْنِ. The second group are the words كِلاَ and كِلْتا when possessed by a ضَمِيْرٌ – (personal pronoun).

Combination 8

The combination is applied to three groups of nouns. Firstly, sound masculine plurals مُسْلِمُوْنَ, مُسْلِمِيْنَ, مُسْلِمِيْنَ. Secondly, to the word أُوْلُوْ this is the plural of ذُوْ. Lastly, numbers in tens from 20 all the way to 90: عِشْرُوْن, ثَلاَثِوْنَ,

Combination 9

This finally combination is applied to only one group of nouns and they are sound masculine plurals to the first person personal pronoun يْ. In the رفع state the و is changed to a ي however in the نصب and جرّ state the ي remains.

And that’s it!

Feel free to leave comments.

Arabic gem: العلم لا يعطيك بعضه حتى تعطيه كلك – ‘Knowledge will not give you even some of it until you give it your all’.

Ma’salaam

Salam brother what an excellent post – just what i was looking for – i’m currently studying Hidayatun nahw and these diagrams is just what i needed. Excellent work, may allah bless you and take you further.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Salam brother sorry the last post i typed in the long email address – anyways excellent posts,brilliant diagrams, may allah bless you – its just what i needed.

LikeLike